Help our local partners realise their vision of hope for their communities

This essay, by James Thorpe, received 3rd prize in the 2016 HART Prize for Human Rights, Senior Essay Category.

The civil war in Uganda has paid no respect to the distinction between military and civilian life, shaping lives across generations and borders. As the conflict wanes, the delicate peace-building process must address the psychological impact of warfare upon communities. The growing narrative from organisations such as the World Bank stresses the importance of ‘social dialogue’ – but it focuses on the interest groups that control labour, ignoring the marginalized who are at the periphery of social provision but have endured years of instability and violence. Art making and art therapy have a valuable role to play in northern Uganda because of their ability to foster catharsis and healing at multiple levels in the community.

Since the early 1980s, power struggles involving government forces and rebel groups have resulted in the death or displacement of millions. Although recent attention has largely focused on the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), Amnesty International (1999) has accused President Milton Obote and his successor Yoweri Museveni of the categorical violation of human rights, meaning that the war has damaged a great number of communities. The conflict has mainly affected northern Uganda but the porous nature of the borders in this part of the country has meant that the successful re-integration of displaced peoples is paramount to rehabilitating communities (Banholzer and Haer: 2014).

Of particular importance to Uganda’s community development is the support of vulnerable young people. The burgeoning youth population could be central to the nation’s development (MoFPED: 2010) but within this lies the challenge of addressing the needs of young people who have participated in or been born into conflict afflicted areas. In many cases, these youths may have been orphaned, abandoned or have fallen outside existing social provision. Uganda has one of the world’s highest rates of children with HIV, which is estimated at around 190,000 (UNICEF:2012). The experience of suffering can truncate a young person’s transition into adulthood.

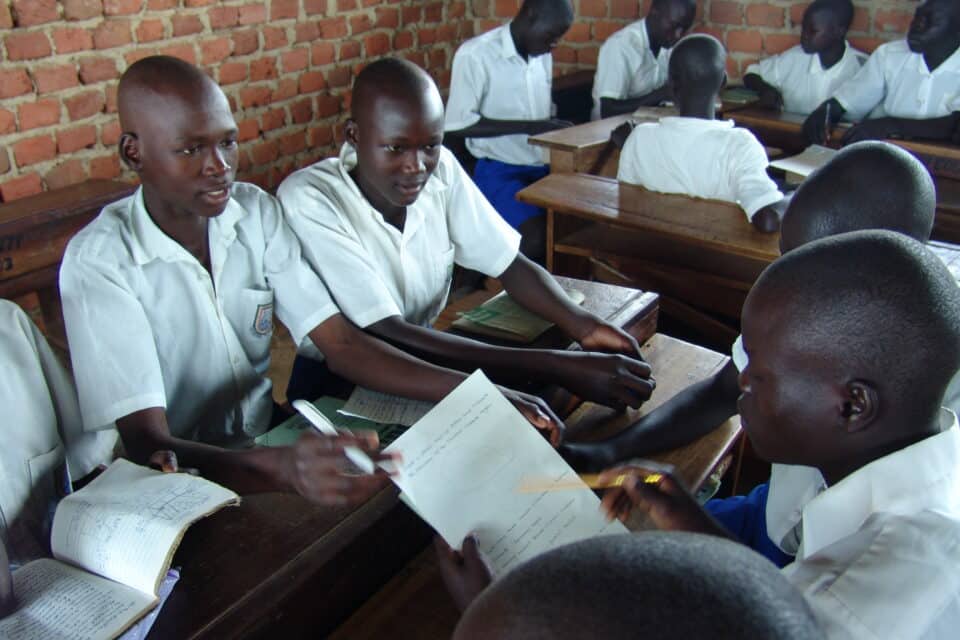

Arts-based education can show young people that their rights are valued by allowing them to present themselves in the way they choose to do so in an environment that is more supportive rather than regulated. In this sense, it is more inclusive than conventional forms of education, which can stifle individuality and place the importance on the teacher rather than the learners. It is critical that the right to an education – a right the conflict has denied to thousands of Ugandans – is upheld as a transformative tool for young people.

Drama, writing, image making and music can be particularly effective amongst younger people, who may respond well to being given practical projects. These forms are easily accessible in relaxed environments, encouraging people to access their own stories and those who surround them. Unlike other forms of education, they do not require a strong level of level of reading or writing ability – thus removing a barrier that may have exacerbated the problems of conflict, crime and lack of employment that have characterized the lives of many young Ugandans during the recent past (IYF:2011).

Drama and theatre can also serve a cathartic purpose in communities by providing an opportunity for audience and participants to explore their experiences more openly. In her analysis of trauma in African narratives surrounding conflict, Norridge makes a strong argument that expression is central to overcoming pain, which, as she writes ‘is often either a result or a cause of another person’s voice’ (Norridge: 2012). Marginalized people are regularly denied a voice due to their lack of power and platform, but drama provides an opportunity for a great multiplicity of voices, experiences and identities to be heard and lived out. Through practice and performance, this art form enables communities to negotiate public spaces together through the production of a collaborative piece. The careful construction of a dramatic piece asks the participants and audience to actively engage with shared issues that affect the community as a whole. This space can deal with pain, poverty and war but it can also access shared hopes and visions for the future. It is crucial that communities are encouraged to express themselves in a public space that may have negative associations due to past events that afflicted the community. The healing power of drama can be nurture civil society by encouraging community participation.

The arts have a unique ability to include multiple layers of the community, assisting a peace-building process that requires different groups to work together. The potential for them to reshape communities is endless, as are the art forms that enable this. Their transformative ability has been observed by Nabarro in post-conflict Sudan: ‘creating visual art and theatre with groups who found it hard to express themselves through words seemed to me, as an artist, to lead to extraordinary things’ (Nabarro: 2012).

As Dinesh (2012) writes, there is a danger that the power of drama may be manipulated at the service of historical propaganda. The 2016 presidential elections illustrate there is a danger that the state may abuse its power to restrict the national dialogue. It is vital that issues of party politics do not supersede the process of rebuilding communities. Yet dramatic forms can be democratic in their nature. Boal enforces the idea that the people must use this medium for themselves: ‘theatre can be placed at the service of the oppressed, so that they can express themselves and so that, by using this new language, they can also discover new concepts’ (Boal: 1979). Crucially, theatre can be a democratic force and whilst external forces may introduce the initiative, the community has the ability to control the process and output (Nabarro: 2014).

The arts facilitate peace building by encouraging communities to reclaim the narrative of past events. Conscious-raising flows into resilience by giving people the opportunity to transform pain into expression. Although healing is an arduous process, the externalization of psychological experiences through creative exchange is an important part in the rebuilding of society in northern Uganda.

Bibliography

Anwo, Joel, Symphorosa Rembe and Kola Odeku, 2009. ‘Conscription and use of child soldiers in armed conflicts’ Journal of Psychology in Africa 19 (1) pp.75-82

Banholzer, Lilli and Roos Haer, 2014. ‘Attaching and detaching: the successful reintegration of child soldiers’ Journal of Development Effectiveness 6 (2) pp.111-127

Boal, Augusto, 1979. Forward and ‘Experiments with the People’s Theatre in Peru’ in Theatre of the Oppressed, London: Pluto Press: pp 120-156.

Blattman, C. and J. Annan, 2010. ‘The Consequences of Child Soldering’ Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (4) pp.882-898

Cummins, Matthew and Ortiz, Isabel, 2012. ‘When the global crisis and youth bulge collide: double the jobs trouble for youth’ Unicef Social and Economic Policy Working Paper http://www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Global_Crisis_and_Youth_Bulge_-_FINAL.pdf

Dinesh, Nandita. 2012 ‘It’s not that simple…doubts, responsibility, theatre and war’ South African Theatre Journal 26:3, 292-302

Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust, Fact Sheet: Uganda, 2014. http://www.hart-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/HART-Prize-for-Human-Rights-Uganda-Factsheet.pdf (accessed 19 February 2016)

International Youth Foundation, 2011. ‘Navigating challenges. Charting hope: A cross-sector situational analysis on youth in Uganda’ http://www.youthpolicy.org/national/Uganda_2011_Youth_Mapping_Volume_1.pdf (accessed 19 February 2016)

Invisible Children ‘History of the war’ http://invisiblechildren.com/conflict/history (accessed 16 February 2016)

Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development ‘Harnessing the demographic dividend: accelerating socioeconomic transformation in Uganda’ 2014 http://uganda.unfpa.org/sites/esaro/files/resource-pdf/02.07.2014.UgDDBrief_Final-final.pdf (accessed 19 February 2016)

Nabarro, Miriam, 2004. Art Therapy and Political Violence: with Art, without Illusion Routledge, London

Tonheim, Milfrid, 2014. ‘Genuine social inclusion or superficial co-existence? Former girl soldiers in eastern Congo returning Home’ The International Journal of Human Rights 18:6, pp.634-645

Uppard, Sarah, 2003 ‘Child soldiers and children associated with the fighting forces’ Medicine, Conflict and Survival 19 (2) pp.121-127

War Child ‘The Lord’s Resistance Army’ https://www.warchild.org.uk/issues/the-lords-resistance-army (accessed February 19 2016)