Help our local partners realise their vision of hope for their communities

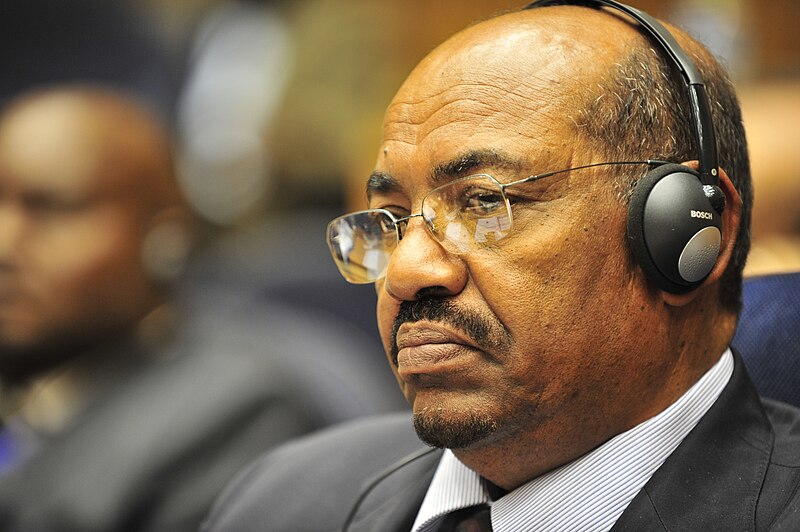

On 31st March 2005, the UN Security Council referred the conflict in Sudan to the ICC Prosecutor. By now, 2 warrants of arrest have been issued against President Al-Bashir, listing ten counts of charges including 5 counts of crimes against humanity and 3 counts of genocide. Historically, this is also the first time the ICC has issued an arrest against a current head of state. However, the execution of the warrant is still pending since no state has arrested or surrendered him to the courts. So why is the ICC so ineffective in its enforcements?

The Conflict of Darfur, Sudan

In 2003, the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and Justice and Equality Movement (Jem) launched an attack as an act against the Government of Sudan. In response, the government led forces to start a counter-insurgency against the rebels. Included in these forces was the Janjaweed, a government-armed and funded Arab militia group. These forces burned hundreds of villages, murdering and raping civilians. The war in Darfur, resulted in 2.7 million people to flee from their homes and approximately 300,000 deaths. Presently, the war has not ended and the crisis is still ongoing.

It must be noted that although Sudan is not a party to the Rome Statute, the ICC was able to gain jurisdiction through the referral from the UN Security Council. On the 5th March 2009, the ICC requested Sudan to arrest and surrender President Al Bashir and on the next day, it requested all its member states to do the same if possible.

The Problem of Enforcement for the ICC

The most fundamental problem that manifests is the lack of cooperation from its members. 9 years after the first warrant was issued, Al-Bashir is still the current president of Sudan. Under the Rome Statute, member states have a duty to cooperate with all ICC arrest warrants. Yet, when President Al-Bashir first stepped off the plane into Chad (a member state to the Rome statute), not only was he not arrested, he was welcomed. By 2016, he has travelled 75 times to 22 countries, many of which are members to the Rome Statute. This illustrates the underlying problem with the court. Since the ICC does not have its own enforcement arm, it depends wholly on member states to execute the warrants. Even though member states are required to cooperate, the failure to do so results in no specific repercussion. This is contrasted with the UN where it is possible to expel a member if principles in the UN Charter are being continuously violated. Within the ICC, no counter ability is given to the courts, resulting in increasingly toothless prosecutions.

Secondly, the lack of support from other international organisations is also incredibly detrimental to the workings of the ICC. The Security Council, for instance, has made little to no effort in persuading members in the UN to help facilitate the execution of these warrants. In fact, the UN provided a helicopter ride to Ahmed Haroun on June 2012 to facilitate his duties as governor of South Kordofan. Haroun, together with Al-Bashir, is one of the four Sudanese men wanted by the ICC. Furthermore, even the Presiding Judge Cuno Tarfusser of Italy has expressed his agitation that since there has been no consequence against states for their failure to comply, ‘any referral to the UN would be futile’. Given the lack of support from the international community, the ICC’s only ability for enforcement is therefore dependent on its members. However, from the analysis above, the members are also unreliable since there is no specific repercussion for the failure to do so. The image of the ICC as a reputable, trustworthy institution is thus damaged into an ineffective, unproductive body.

Another problem that the ICC faces is in the conflicting and unclear provision in the Rome Statute in regards to immunity and compliance. Article 98(1) gives diplomatic immunity and article 98(2) provides that states do not need to comply if they have prior agreements. Thus, this adds confusion to member states as on one hand, the ICC can prosecute anybody including heads of state, but at the same time diplomatic immunity can be granted. The confusing provisions is also a reason for the non-compliance by member states. As the African Union (AU) stated in the decision they issued to their member states, Al-Bashir has immunity as a sitting head of state and hence cannot be prosecuted. Furthermore, since countries that Al-Bashir has visited such as Chad are members of the AU, they can claim that since the two positions conflict with one another, they do not need to comply with ICC decisions. This causes grave concerns since the legal provisions are unclear when this diplomatic immunity can be removed, nor does it provide provisions to remedy the case of conflicting interests. Since Sudan is not even a member state, it is argued that if the ICC ignores his diplomatic status, it is enough to constitute as an infringement upon the national sovereignty of Sudan. Therefore, the lack of clarity in the Rome Statute itself, hinders the effectiveness of enforcement.

Possible Solutions

Although it is argued that a police force could be established to give the ICC power for its own enforcement, the likelihood for this to materialise is low. This is due to the foreseeable high cost in establishment and maintenance of the force, its uncooperative member states and the lack of support from other international organisations. Therefore, a much better way would be to change the laws from the inside. The uncertain legal provision in Article 98 has to be changed in order to prevent member states like Chad and Kenya to use them as excuses for their inability to arrest and surrender Al-Bashir. By being more specific and limiting the conditions in which these provisions can be used, the flexibility of the statute can become more narrowed.

Another method to improve the enforcement abilities of the ICC is by giving it more powers such as expulsion (temporary or permanent) or sanctions. By expelling member states on the basis of non-compliance, members are more likely to conform to this basis. However, there is a possibility that expulsion might be seen as too harsh, so suspension powers should also be recognised. In addition to this, sanctions from the international community should also be an avenue given to the ICC. By imposing sanctions on non-cooperative members, it gives the members a real threat to comply with the arrest warrants issued by the ICC. On the other hand, this power must be limited. The sanctions imposed must only be proportionate and not arbitrary. This way, countries are only punished reasonably and their national sovereignty is respected.

Conclusion

There have been 13 cases of non-compliance by member states for the arrest of the four Sudanese men wanted by the ICC. In particular, the failure to arrest Al-Bashir is the reason for 10 of these cases. Without the accountability from the international community, he becomes increasingly fearless each time. It must not be forgotten that even though this man has 10 charges against him, the ICC cannot try him unless he is present in the court. Only with a change in legislation and an increased support and compliance from the international community, can justice be rightly served for Omar Al-Bashir.

For more information on Sudan and HART’s efforts there, click here.