Help our local partners realise their vision of hope for their communities

The plain truth for countries like Uganda, especially among its rural regions, is that health, despite being a major cause for concern, is not met with adequate funding. Yet it is literally a matter of life and death. Cited throughout HART’s reports and literature, it is important to realise that without healthcare, people die.[1]

HIV in Uganda

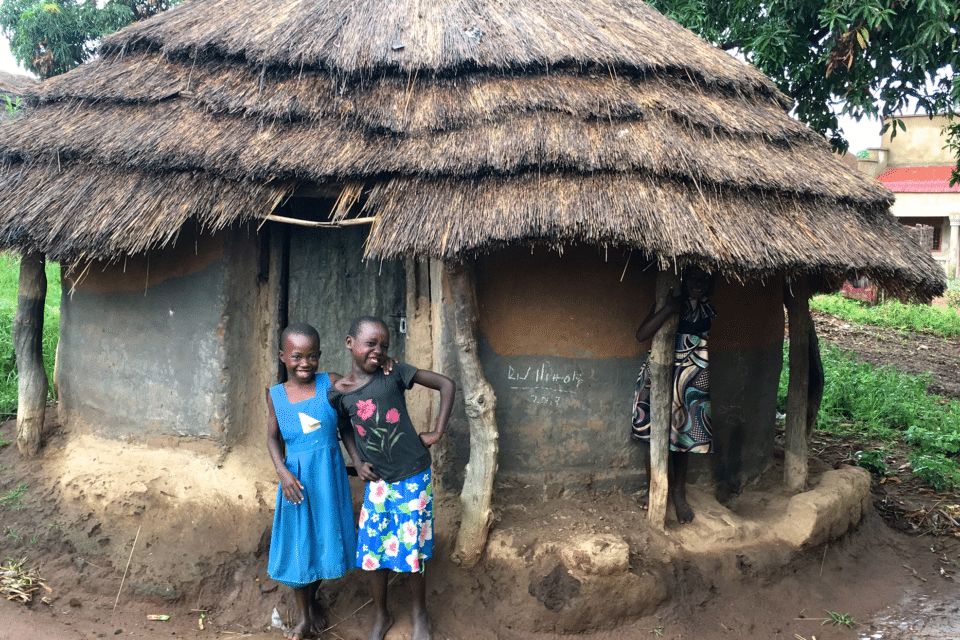

Uganda, a diverse, East-Central African country that gained independence in 1962, has had a damaging relationship with HIV. A region particularly affected by HIV is the north and north-east of Uganda, which tends to be less developed than pulsing urban cities like Kampala. Slightly more sparsely populated but with higher levels of poverty, these rural Ugandan regions have also suffered from insufficient health care. Lack of economic opportunities for skilled physicians often leads to a type of ‘brain drain’ where doctors leave in search of more financially sustainable work. The density of physicians in Uganda was recorded at 0.09 physicians per 1000 of the population in 2015, a ratio too low (according to the World Health Organisation) to fully satisfy the primary healthcare requirements of a country.[2]

A brief reflection on the current health situation in Uganda

As of 2017, there were an estimated 1,300,000 people (both adults and children) living with HIV in Uganda, yet only 72% of them received antiretroviral treatment (ART) in that year. In 1998, Uganda made history when it became the first Sub-Saharan country to succeed in reducing HIV infection by a large extent.[3] Still, an urgent problem present in Uganda is the children left destitute by HIV / AIDs. Statistics from 2017 declare an estimated 560,000 children between 0 and 17 were left as orphans due to AIDs.[4]

The role of the government

Despite the fact that the Ugandan government has been rattled by periods of deep conflict and trouble, decisive actions are being taken to reduce HIV infection and better its prevention. The work is not perfect, but it is a start. Below are a couple of initiatives whose eventual aim is to prevent the grip of HIV over this nation full of promise.

Uganda’s ABC programme[5]

- Unlike other campaigns that promulgated the use of condoms as a practical method to prevent the HIV infection during sexual intercourse, Uganda took a threefold approach: Abstinence (reducing chance of infection), Be Faithful (discouraging multiple casual sexual partners) and Condoms (preventing bodily infection).[6]

- There are still many disputes over the effectiveness of these sorts of measures or even if ‘statistics’ concerning HIV in Uganda and other nations are accurate.[7]

Prevention of the Transmission of HIV from Mother to Child

- With a high fertility rate of 5.62 children born to each woman (2018)[8], mother-to-child transmission can be a cause of HIV infection and it is vital to prevent it.

- This can be something as technically simple as switching to formula milk rather than breast milk (although this is practically harder when it comes to extremely poor and rural regions of Uganda) as well as administering the correct medicine to HIV positive expecting mothers.[9]

The role of the local community

The impact of HIV in northern and rural Uganda is as much psychological, mental and emotional as it is physical. It can be the case that the cycle of HIV infection continues indefinitely because of culturally-ingrained and community-based prejudice and discrimination against those who are HIV positive.

Discrimination is targeted at three main groups: men who have sex with men, sex workers and people who inject drugs. The issue is that these are people at higher risk of contracting HIV in the first place. Fear of discrimination makes them less likely to speak openly about their personal situation to health professionals, which in turn increases the risk of undetected viral infection, thus allowing HIV to go unnoticed and give rise to further illness. This means that people at risk of HIV do not acquire the help they need, and even when they do have antiretroviral drugs at their disposal, they may still face debilitating discrimination in their environment.

In this way, while it is necessary to provide basic education and medical supplies needed to prevent the spread and worsening of HIV, there still needs to be an upheaval of social values within each village and town so those often marginalised by society feel confident to come forward and seek help. There is no practical use having the medicine in place when no one is willing to admit that they might need it.

The role of HART

The main way in which HART is contributing to better lives for Ugandans both with and without HIV is through continual support and encouragement of the PAORINHER programme in Patongo in the north of the country.

The theme of the organisation states: Poarinher the champion against illiteracy, HIV / AIDS and child abuse.

In 2018, achievements at the centre include:

- 371 HIV+ children received ART drugs

- 320 families with HIV+ children received nutritional training

- 100 additional family members were treated for sporadic infections

- 350 new HIV+ family members received agricultural and poultry training

This sort of work is exactly what we need to unite communities rather than divide them due to the stigma and misconceptions surrounding HIV. Solving a crisis like HIV / AIDs is not a matter of prescribing some drugs and walking away. It is a multi-faceted effort encompassing education, reformulation of prejudiced beliefs, medical prevention and effective treatment.

Okot p’Bitek, a Ugandan poet, wrote in his Song of Ocol[10]:

Tell me

My friend and comrade,

Do you remember

The night of uhuru*

When the celebration drums throbbed

And men and women wept with joy

As they danced,

Hands raised in salute

To the national flag?

*Swahili; can be translated as freedom.

Our hope is that one day the Ugandan people will join together in freedom, when the scourge of HIV is blotted out from the face of their nation.

[1] For more information about the HIV crisis in Uganda, see the Health section in HART’s Impact Report 2016. https://www.hart-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/HART_Impact_report_A5_WEB.pdf (HIV: Ending the Stigma)

[2] Source: CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html

[3] Source: Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/place/Uganda/

[4] Source: UNAIDS Country Factsheets 2017. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/uganda

[5] For more information (and an alternative perspective) on Uganda’s ABC programme, see this essay by Constantin Gouvy: https://www.hart-uk.org/blog/how-the-structural-hindrance-of-the-global-aids-responses-behaviour-focus-affects-the-formulation-of-comprehensive-hiv-aids-prevention-programmes-in-uganda-and-sub-saharan-africa-hart-prize/

[6] HIV / AIDs prevention in Uganda: why has it worked? See: https://pmj.bmj.com/content/postgradmedj/81/960/615.full.pdf

[7] Ibid.

[8] Source: CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html

[9] Source: Avert – Global Information and education on HIV and AIDs. https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/uganda

[10] Source: Scottish Poetry Library. https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/song-ocol/

Other Resources:

- https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2010/july/20100727prafricanunion

- https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/uganda

- https://www.hart-uk.org/paorinher/

- https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2018-05-14/debates/EA7B67F0-52CC-4820-BBEC-B5D2324B9E13/Nursing#contribution-CF77F652-041C-4347-9E80-A207DFAACFC5

- https://www.hart-uk.org/news/northern-uganda-visit-report/

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hiv-and-aids/

- https://www.britannica.com/science/HIV

- https://www.britannica.com/science/AIDS

- https://www.hart-uk.org/blog/can-overcome-stigma-hivaids-northern-uganda/

- https://www.hart-uk.org/blog/paorinher-project-northern-uganda/

- http://www.learningfromuganda.org.uk/schools-projects/culture.html

- For more information about what HART did in 2017 to combat the Ugandan HIV crisis, see the Uganda section of the Impact Report 2017. https://www.hart-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/HART_Impact_report_2018_DIGI.pdf